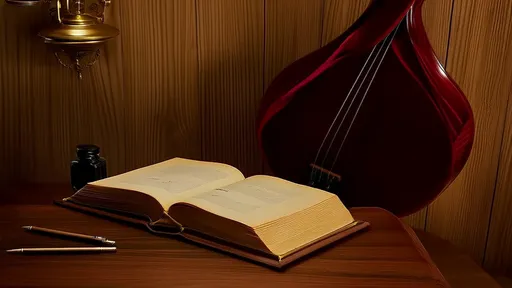

The discovery of an unpublished manuscript from any significant musical figure sends ripples through the academic and artistic communities, offering a rare glimpse into the creative laboratory of a master. Such finds are not merely about the notes on the page; they are about context, process, and the potential to recalibrate our understanding of a composer's oeuvre and their historical moment. The study of these documents is a delicate archaeology of sound, where every smudge, every hesitation, and every alteration tells a story that the finished, published work often conceals.

When a previously unknown manuscript emerges from a private collection, an archive's uncataloged depths, or even an attic, the first challenge is one of authentication. This is a forensic process, combining musicological analysis with historical detective work. Experts examine the paper—its watermark, weave, and size—to date it and trace its origin. The ink and handwriting are scrutinized, compared against known examples of the composer's script from the same period. The musical content itself is the most telling evidence; its stylistic fingerprints, its harmonic language, and its thematic material must align convincingly with the composer's established body of work, while perhaps also showing the seeds of future developments or echoes of past ones.

Beyond proving its legitimacy, the scholarly work delves into the manuscript's provenance. Who owned it? How did it pass from the composer's hand to its present location? Each step in its journey can add a layer of meaning. A manuscript gifted to a patron might contain subtle flatteries or concessions, while one kept by the composer could be a raw, unvarnished experiment never intended for public eyes. Correspondence, diaries, and financial records from the era are scoured to piece together this narrative, often revealing fascinating networks of influence, friendship, and patronage that supported the musical culture of the time.

The content of the manuscript is, of course, the central fascination. It might be a complete work, unknown in any other form, forcing a reevaluation of the composer's output. Is it a masterpiece that was suppressed, lost, or simply forgotten? Does it fill a gap in their stylistic evolution, showing a transition between two known periods? Alternatively, it might be a preliminary version of a famous piece. Comparing the manuscript to the published score can be revelatory. Early drafts might contain extended passages that were later cut, different instrumentation, or alternative melodic lines. These deleted scenes of music history reveal the composer's second thoughts, their struggles, and their refinements. What was deemed unnecessary, too provocative, or perhaps too technically demanding? The reasons for these changes speak volumes about aesthetic tastes, practical constraints, and the composer's own self-critical ear.

Furthermore, these manuscripts often serve as a crucial link to the performative aspect of music. Unlike a sterile printed score, a composer's holograph is full of life. It may contain articulation marks, dynamic indications, or tempo directions that are more nuanced or even contradictory to those found in the standardized published editions that musicians have used for centuries. For performers, this is akin to receiving instructions directly from the creator, offering a more authoritative guide to the composer's intentions. It can challenge traditions and invigorate interpretations, leading to performances that sound fresher and closer to the source.

The impact of such a discovery extends far beyond the notes. It can alter the critical reception of a composer. A previously unknown work from a composer's "late period" might deepen our appreciation of their mature genius, while an early work might shed light on their influences and formative struggles. It can also have commercial and legal implications, affecting copyright status and the repertoire available for recording and performance. Most importantly, it adds a new piece to the immense, interconnected jigsaw puzzle of music history, helping us to better understand not just one individual, but the entire cultural ecosystem that produced them.

In the end, the study of an unpublished manuscript is a profoundly human endeavor. It is an attempt to bridge time and connect with the moment of creation. We peer over the composer's shoulder, witnessing the act of invention itself—with all its false starts, its flashes of inspiration, and its diligent labor. It is a reminder that the great works we revere were not immaculately conceived but were built, note by note, through a process that was often messy, uncertain, and profoundly personal. These manuscripts are not relics; they are conversations waiting to be continued, and their rediscovery ensures that the music, and the spirit behind it, continues to evolve and resonate with new generations.

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025