In the hushed galleries of the Metropolitan Museum, a new installation quietly dismantles our perception of reality. Double Reflection: The Eternal in Infinite Mirrors is not merely an exhibition; it is a philosophical inquiry rendered in glass and light, a silent conversation between the viewer and the void. Curated by the visionary Elara Vance, this collection of works from a dozen international artists explores the profound, often unsettling, dialogue between the self and its countless replicas in the mirrored abyss.

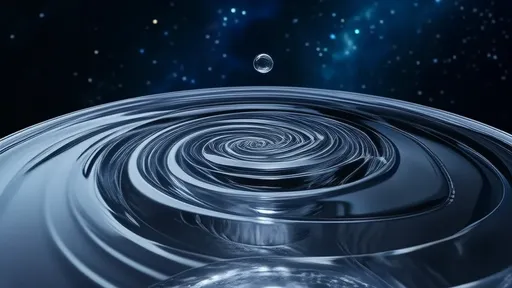

The central piece, from which the exhibition draws its name, is a creation by the reclusive Japanese artist Kenji Sato. Upon entering a seemingly plain, dark room, the visitor is met with two flawless, opposing mirrors. A single, suspended light bulb hangs between them, its light both the subject and the object of the infinite regression it creates. The effect is instantaneous and breathtaking. One does not simply see a long tunnel of lights; one is physically inserted into a cosmos of recursive self, stretching into a theoretical eternity. The ‘you’ in the immediate foreground is solid, familiar. But the ‘you’ ten reflections deep is a stranger, a pixelated ghost distorted by the imperceptible flaws in the glass and the cumulative journey of light. It is a powerful metaphor for the modern self, endlessly curated and reflected back at us through digital avatars and social media feeds, each iteration further removed from the original source.

This theme of fractured identity is echoed, quite literally, in the work of Spanish sculptor Mateo Cruz. His “Fractured Echoes” employs broken, warped, and pieced-together mirrors arranged in a sprawling, maze-like structure on the floor. There is no single, unified reflection to be found. Instead, the viewer’s image is shattered, captured in a hundred different fragments, each showing a sliver of a whole that can no longer be perceived directly. One fragment captures a worried eye, another the tense line of a shoulder, a third the hesitant gesture of a hand. Cruz forces us to confront the uncomfortable truth that our identity is not a monolithic whole but a collage of these disparate, often contradictory, parts. We are not one self but many, and the quest for a singular, authentic identity may be the greatest illusion of all.

Beyond the psychological, the exhibition delves into the metaphysical. Iranian-American artist Layla Parviz’s “The Observer Effect” is a minimalist’s dream and a physicist’s playground. A single, high-precision mirror is placed at the end of a long, dark corridor. As the viewer approaches, their reflection sharpens into focus. However, integrated into the frame are delicate sensors that detect proximity. The closer one gets to truly see oneself, the more the mirror’s surface subtly fogs over, obscuring the details. It is a brilliant, interactive manifestation of the quantum principle that the act of observation alters the state of the observed. Parviz suggests that the same is true of self-examination; the harder we look inward in search of a definitive truth, the more we potentially change or obscure the very thing we are trying to see. The self is not a static portrait to be analyzed but a dynamic process, forever altered by the gaze upon it.

The most hauntingly beautiful piece may be Chilean artist Rafael Torres’s “Chronos Untangled.” Using a complex arrangement of semi-transparent mirrors and timed, fading LEDs, Torres creates the illusion of time-lapse within a single static view. Stand before it, and you see not only your current self but faint, ghostly after-images of where you were just seconds before, and even fainter pre-images of where you might move next. It creates a palpable sense of time as a fluid, simultaneous medium rather than a linear progression. Your past, present, and potential future selves coexist in the same space, a silent council of who you were, are, and could be. It evokes a deep, almost melancholic nostalgia for moments that are both immediately past and yet to come, highlighting the eternal present tense of consciousness trapped within the flow of time.

Elara Vance’s curatorial genius lies in her sequencing. The journey is deliberate. It begins with the awe of infinite possibility in Sato’s work, moves through the fragmentation of Cruz, confronts the existential dilemma in Parviz’s piece, and finally arrives at the temporal dissolution of Torres’s installation. The visitor is led on a path from external perception to internal deconstruction. “Double Reflection” argues that the infinity we see in the mirror is not just an optical trick; it is a parallel to the infinite complexity within the human psyche. The mirrors do not create something new; they reveal the boundless, often chaotic, reality that already exists.

The exhibition has unsurprisingly ignited fervent discussion among critics and philosophers alike. Dr. Alistair Finch, a cognitive philosopher from Cambridge, remarked, “This is not art about seeing. This is art about ‘seeing that you are seeing.’ It meta-cognizes the very process of perception and self-awareness. The mirror, the oldest and simplest tool for self-recognition, is finally being used to show us its own inherent deception.” The show challenges the very foundation of how we construct reality and identity in an age of superficial reflection. It asks if the true eternal is not found in some distant heaven, but in the endless, recursive loop of self-perception that defines our every waking moment.

In a world saturated with images and obsessed with self-presentation, Double Reflection: The Eternal in Infinite Mirrors serves as a necessary, sobering pilgrimage. It strips away the vanity and the vanity’s medium, leaving the viewer alone in a quiet room with an infinite number of themselves. The final reflection, the one that stays with you long after you’ve left the museum, is not in glass, but in mind. It is the uncanny and eternal echo of a self forever multiplied, forever sought, and never completely grasped.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025