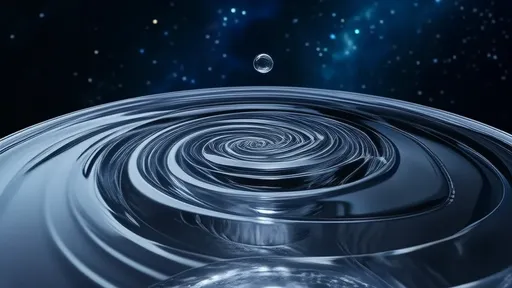

In the quiet corners of our homes and the sprawling expanses of nature, a silent, hydraulic ballet unfolds daily—the journey of water from soil to stem, from root to leaf. This process, capillary action, is one of nature’s most elegant mechanisms, a physical phenomenon that breathes life into the plant kingdom. While the act of watering plants may seem mundane to the casual observer, it is, in fact, a sophisticated interplay of physics, biology, and chemistry—a story of how life sustains itself against the pull of gravity.

Capillary action, or capillarity, refers to the ability of a liquid to flow in narrow spaces without the assistance of, or even in opposition to, external forces like gravity. It is the same principle that allows a paper towel to soak up a spill or a sponge to draw water upward. In plants, this phenomenon is harnessed through an intricate network of microscopic tubes called xylem, which function as nature’s plumbing system. These vessels, often no wider than a human hair, are engineered to facilitate the ascent of water from the roots to the highest leaves of towering trees.

The driving forces behind capillary action are adhesion and cohesion. Adhesion is the attraction between water molecules and the walls of the xylem vessels, while cohesion is the mutual attraction between water molecules themselves. Together, they create a continuous column of water that can be pulled upward through the plant. As water evaporates from the leaves through tiny pores called stomata—a process known as transpiration—it creates a negative pressure that draws more water from below, much like drinking through a straw. This transpirational pull, combined with capillary forces, enables water to defy gravity and reach astonishing heights.

But capillary action is only part of the equation. The very structure of the xylem is a marvel of biological engineering. The walls of these vessels are composed of cellulose and lignin, materials that provide both strength and hydrophilicity—an affinity for water. This hydrophilic nature ensures that water adheres to the walls, facilitating its upward movement. Moreover, the diameter of the capillaries plays a critical role; narrower tubes enhance capillary rise due to increased surface tension relative to volume. It is a delicate balance, perfected over millions of years of evolution.

For gardeners and plant enthusiasts, understanding capillary action transforms the routine task of watering into an act of profound connection with nature. When you pour water into the soil, you are initiating a chain reaction that relies on these very principles. Moisture is drawn into the root hairs through osmosis, entering the xylem and beginning its ascent. The health of this system depends on adequate hydration; too little water, and the cohesive column can break, introducing air bubbles—a condition known as embolism—that can obstruct flow and jeopardize the plant’s survival.

Different plants have adapted to optimize capillary action in diverse environments. Desert succulents, for instance, possess shallow but extensive root systems that quickly absorb scarce rainwater, while their reduced leaf surface minimizes transpirational loss. In contrast, rainforest trees develop deep root systems and broad leaves to maximize water uptake and transpiration, leveraging capillary action on a grand scale. Even the texture of the soil influences capillary rise; sandy soils with larger particles exhibit weaker capillary action compared to clay soils with finer particles, which can draw water higher from underground sources.

The implications of capillary action extend beyond natural ecosystems into agriculture and horticulture. Farmers utilize irrigation techniques that mimic these principles, such as drip irrigation, which delivers water directly to the root zone, reducing waste and maximizing efficiency. In controlled environments like greenhouses, substrates are often designed to enhance capillary rise, ensuring consistent moisture distribution. Understanding these dynamics allows for more sustainable water use, a critical consideration in an era of growing environmental awareness.

Yet, capillary action is not infallible. External factors such as temperature, humidity, and soil composition can influence its efficacy. High temperatures accelerate transpiration, increasing the demand on the capillary system, while high humidity slows it down. Saline soils, common in arid regions, can disrupt osmosis at the roots, reducing water uptake and straining the plant’s hydraulic mechanisms. Thus, successful plant care requires not only knowledge of capillary action but also an awareness of the broader environmental context.

In a world increasingly concerned with sustainability, the lessons of capillary action are more relevant than ever. This natural mechanism exemplifies efficiency—moving water without external energy input, relying solely on the properties of matter and the ingenuity of biological design. It reminds us that sometimes the most advanced solutions are those that nature has already perfected. For scientists and engineers, capillary action inspires innovations in fields ranging from microfluidics to materials science, where mimicking these principles leads to breakthroughs in technology.

At its heart, the story of capillary action is a testament to life’s resilience and adaptability. It is a process that connects the smallest herb to the tallest redwood, a universal thread in the tapestry of the botanical world. Every time we water a plant, we participate in this ancient dance—a dance of molecules and forces that nourishes and sustains. It is a humble reminder that even the simplest acts are underpinned by profound natural laws, and that in understanding them, we deepen our appreciation for the intricate beauty of life on Earth.

So the next time you tend to your garden or admire a forest, remember the invisible forces at work. Capillary action is more than a scientific curiosity; it is a vital pulse, a silent river flowing upward, defying gravity to deliver the essence of life itself.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025